Churches offering hope...

For the first time in months, it doesn’t feel like we’re kidding ourselves there is light at the end of the tunnel – it feels like we can actually see better times ahead, writes Gwyn Williams.

COVID HAS been tough for everyone. Christians have been no exception. Glitchy online services; squeezed finances; isolated congregations; much-loved church family members lost. There have been days of doubt and anger, where trust and peace have felt like they have been in conflict with one another.

This last year has been really painful for lots of us. But it has also been a time of incredible hope.

The pandemic hit and churches stepped up to the plate: they adapted and went online; they became hubs for food banks; and centres for the vaccine rollout.

According to a report released last month, the Church has provided 5 million meals every month of lockdown to those in need. Many with dwindling congregations have seen their numbers swell, churches have pulled together to provide for the needs of their communities. They have done an amazing job of responding to the crisis.

But where do we go from here? What about when the immediate crisis is over?

COVID may come to an end but its devastating consequences are far from over. One in six new universal credit claimants is unable to afford enough food for their families. A study by The Legatum Institute last November revealed that almost 700,000 people had been driven into poverty by COVID, including 120,000 children.

Trapped without hope

When we are over the worst, and ‘normality returns for the majority, there will still be so many vulnerable, so many in need of hope.

There is a lot to be commended in the Church’s response to COVID but there is also a lot to learn. It would be easy to keep firefighting, trying to meet the never-ending tide of people’s immediate needs. But now is a time to step back and reflect on how the Church can serve their communities for the long run.

Firstly, we need to assess our motivation. We need to ask ourselves if our efforts have become more about our ‘good works’ than about the loving people like Christ did. It is people, not projects that need to be at the heart of the Church’s response to poverty. We need to view the people we serve holistically and truly engage with what they need most.

Many people in poverty are unable to see beyond their current circumstances. I have visited schools in deprived areas across the UK and teachers report time and time again that the main problem they face is that children cannot see a sense of value in attainment. They feel trapped, without hope.

The Psalms are littered with reminders of God’s heart for the vulnerable and afflicted. But not just his heart for them, his commitment to them. Psalm 9 verse 18 reads: ‘But God will never forget the needy; the hope of the afflicted will never perish.’

The Church has done incredible work in meeting immediate needs, and we must continue to do so. But now we need to step out from behind the coffee table or the foodbank station to build relationships. We must take people on a journey. A journey from a place of survival to one of safety and security. A journey that gives them hope.

Bringing hope and building relationships on top of what you are already doing may feel like a tall order in this time. And it is. But the Church doesn’t standalone. If we are to focus on effectively meeting the long-term needs of the vulnerable, we need to do it alongside the rest of our communities.

The Church is a vital part of the picture. But it is still only part of the picture.

Symphony of churches

One of the most encouraging impacts of lockdown has been churches working with organisations across the community to help the vulnerable and take them on this journey of hope. In a survey of more than 900 churches, over 90% of churches had been helping the vulnerable during the lockdown and 72% had been working in partnership with the council, charities or other churches (Changing Churches Report: Responding to the Coronavirus crisis). This is a phenomenal statistic, and something needs to continue and grow when the lockdown is over.

We need to reach out to the councils and charities in our local area. To listen with humility to the needs they are seeing around them and the gaps there are in resources and provision. That is the vision of The Halo Centre, which recently opened in Coventry. This centre hopes to be one of many across the UK that equip not just churches but entire communities. Creating a symphony of churches, projects and council to impact the city for good.

If we are going to reflect God’s heart for the vulnerable, we need to lay aside our individual reputations as churches; we must trust him, build relationships and partner with others. That is how the Church will bring the hope of God into the lives of broken people.

Gwyn Williams has been UK Operations Director for Feed the Hungry for the last 10 years, where he delivers and manages community projects in the UK and internationally.

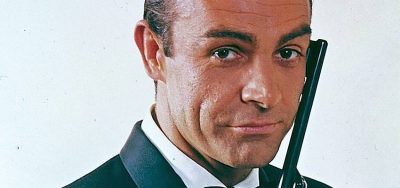

Bond shaken and stirred

Egg absence hits Easter

UK's best 'secret' beaches

Top films of the 80s

The curse of 'busy-ness'

Are you like Sorted’s Miles Protter, a man who always has to be busy? If you are, it might be time to do some valuable and long-overdue soul-searching.

I HAVE always thought of myself as a productive person: disciplined, hardworking and busy.

It’s how I’m wired. I got it from my Dad, who’d be in his office from early hours wearing only his pants, hair askew, talking loudly to someone in German as I walked by to breakfast. Later as I set about the return journey, he’d be talking to someone in Italian. Before leaving for school, I’d pop my head in to say goodbye and receive a little wave from the middle of his conversation.

It didn’t stop there. Dad had one of the earliest carphones. It was a clunker handset, allowing him to yammer away the moment he turned the key. He was a ‘busy-ness’ addict for sure.

As a dreamy, book-loving adolescent I didn’t stand a chance. School and university tutored me in ambition. I became a banker, working all hours to make my mark. And just like Dad, I’d be on the phone early, or late, to somewhere else, cramming yet more into my day.

Busy-ness was a badge of honour, my highest definition of success. I had become an addict too.

But the stress, exhaustion and absence affected my marriage and family, so I quit. An enormous space opened up for me like the silence enveloping you after a loud concert. I served in the community, made dinner and took my daughter to and from school.

Feed the machine

A few years later, I invoked busy-ness back into my life by accepting a leadership role in a consulting firm.

HQ in Texas demanded we ‘feed the machine’ with daily, weekly and monthly data, calls, reports and visits. There was also the ‘real work’ of attending to clients, recruiting and training staff, and developing new products. With no room left, the only way to get my attention was via an emergency – like a client threatening to leave.

What didn’t get my attention were the crucial things grumbling along just below my pain threshold, like the fact our growth was built on a boom with less than two years to run and an insufficient pipeline of new products or clients to replace it. And poor systems; and not hiring local talent.

Alas, I did not address these issues properly even though I knew we’d suffer later, generating a kind of cognitive dissonance, a gloom that descended even when things were good because of the crises looming just outside my peripheral vision.

My family life was suffering so I left that job too and once again a beautiful space opened up. My wife and I went for a six-week hike and discussed matters untouched in 25 years. I visited friends and cooked a lot. I read books and went to the beach.

Recently, I wondered if being older, wiser, self-employed and working from home had banished the curse of busy-ness? To my regret, I found the answer to be 'no'.

It appears I am still on automatic, filling every available hour with stuff that has to be done, rushing from one thing to the next, overwhelmed by floods of messages and reminders that feel like ‘Whack-a-Mole’. I then regret wasting time on trivialities. It produces a hyper feeling of productivity, but in reality, it’s just distraction and stress.

For example, instead of doing the work required to complete this article in the three-hour block set aside in my calendar, I wasted time thinking up a title, answering emails, polishing the opening sentence, sending out an invoice and reading pages of background material to find great quotes I’ll never use. I was busy on things other than the most important thing.

No magic solution

I eventually gave myself a good scolding and got writing, working late to meet the deadline. Then I lay awake at two in the morning thinking about stuff not done.

And with so little time to think qualitatively, I do the important things badly – like replying to a friend’s message about his parent’s illness by emailing a brief, one-sentence platitude filled with misspellings.

Unfortunately, I have no magic solution.

Battling with myself doesn’t work. I can’t ‘manage it' with a calendar. The most effective way has been to remove myself entirely when it gets too much. But I can’t always do that so, as they recommend in the Twelve Steps programme advocated by organisations committed to alleviating behavioural addictions, I’m being honest and sharing my struggles. Critically, I am asking myself: ‘What’s really important here, Miles?’

Do you battle with busy-ness?

If the answer is a resounding ‘yes’, ask yourself these questions: is it really worth it to get that last little thing done? What is it costing you? What is really more important?

Miles Protter has worked with thousands of people as a mentor, consultant and coach for more than 30 years. His executive mentoring practice is called The Values Partnership, and he also founded Men’s Business. He lives in Perth, Western Australia with his wife Deborah and their daughter, Lily.

Klopp's in 'good hands'

The Boss is the best

Stars offer help to needy

Keep football in its box